REMINESCENCES OF A JOURNEY TO LITHUANIA

In

un’intervista Mekas racconta che fu grazie a

The Brig e al favore della critica, che il regime sovietico incominciò ad

interessarsi alla sua persona e alle sue opere.

Il

film fu presentato al Moscow Film Festival come un importante lavoro,

antimilitarista e anticapitalista, mentre alcuni corrispondenti furono mandati

ad intervistare lui e la madre.

“Suddenly

I felt I had enough clout to apply for a visa to visit Lithania. Since I had

been invited to the Moscow Film Festival, I thought I would ask to be permitted

to go to Lithania also, to visit my mother.

For

over a decade I had not been allowed even to correspond with my mother. I had

written some poems against Stalin, so I was a criminal. My brothers were thrown

into jail because of me, and my father died earlier than he would have, because

of that. My mother’s house was being watched for years, really, by the secret

police. They hoped thet one day I’d come home and they‘d get me. My mother

told me that in 1971. There was not a night, during my visit home, when I

wasn’t prepared to jump out the window, to run from the police if they decided

to come after me. And this in 1971, many years after Stalin’s death.”[1]

Dal

momento che il governo di Mosca si era dimostrato favorevole alla visita di

Mekas, anche la Lituania lo riammise in patria, permettendogli di incontrare i

parenti e pubblicando, per la prima volta una raccolta di sue poesie.

“Suddenly

I could film whatever I wanted. Usally visitors are not permitted to go into the

villages; they stay around their hotels. I was offered an official film crew to

do whatever I wanted, but I said ‘I will be using my Bolex; I don’t want any

film crews.’ They found it strange, but they gave in. They have their own

crews around much of the time, making their own film about me and my mother _in

Cinemascope.They sent me a print, which I have.

I

also shot some Moscow footage on that trip, but I haven’t used it so far.”[2]

Reminiscences

of a Journey to Lithuania

(84 min.) rappresenta il resoconto filmato di questo viaggio: “he uses

the occasion of his first return to Lithuania in twenty-seven years to construct

a dialectical meditation on the meaning of exile, return, and art”.[3]

Esso

si compone di tre parti: la prima contiene le riprese che Mekas girò nei primi

anni di esilio in America, la maggior parte si svolgono tra il 1950 e il 1953.

La seconda parte fu girata nell’Agosto del 1971, in Lituania, mentre la terza

è composta da riprese fatte a Elmshorn (la città in cui durante la guerra, i

fratelli Mekas iniziarono le loro disavventure), e a Vienna dove Jonas fece

visita ad alcuni amici.

REMINISCENCES

OF A JOURNEY TO LITHUANIA[4]

by

Jonas Mekas

PART

ONE

The

Fall trip into the woods

Square.

Winter in Central Park.

Square.

Fall in Central Park.

1950

Adolfas

making faces.

OUR

STREET IN BROOKLYN (WILLIAMSBURG)

HENRY

MILLER GREW UP HERE

Myself

walking with sunglasses.

Square.

Workers in the truck.

PARENTHESIS

A

GATHERING OF DP’S IN STONY BROOK (1951)

In

Stony Brook. People. Dancing.

Square.

Group singing in the woods.

Picnic

in Brooklyn. Accordionist.

MYSELF,

IN 1950, JUST AFTER GETTING MY FIRST BOLEX

Square.

Myself after getting Bolex.

PARENTHESIS

CLOSED

Knocking

at the door. Never.

Square.

Time Quare traffic.

Leo

drinking wine.

Square.

Color shot in Brooklyn.

DP’S

AT THE PIER 21 NEW YORK (1950)

At

the Pier 21

Color

shot myself on the roof.

Hudson

River party.

Square.

Myself shaking head.

Adolfas

in Times Square. Close-up of myself.

Adolfas

in Munich.

1952

Square.

100

GLIMPSES OF LITHUANIA

1-Legs

in water. Lady with apple.

2-Flowers

in the garden.

3-Fields

from the car.

4-

“

“ “

“

5-

“

“ “

“

6-

“

“ “

“

SEMENISKIAI

(CENTER OF THE WORLD)

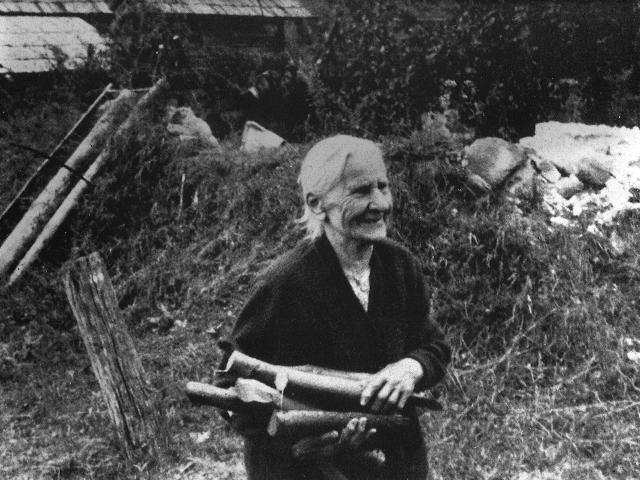

7-MAMMA

(BORN 1887)

8-Dada

comes with his hat. Aunt gathers berries. Pola offers berriers to Mama.

9-Dada

with his two sisters

10-Mama

watches Dada and Pola dance.

11-Myself

and Mama by the door.

12-Our

cousin by the well.

13-Dada

prepares to go to church.

14-Mama

holds hands full of raspberries.

15-At

the church.

16-The

house we lived in. Window. Lake. Mama walks.

17-

Driving to the village.

18-

Entering Semenis. Arriving at the house. Cat. Cat runs away. Cat rolls the

ground.

19-

Woman with the sheep. Adolphus drinks water from the well.

20-Sunset.

Indoor shots. Going to the neighbour for milk

and beer. In the field.

21-At the neighbour. Drinking beer. Mother of Jonas. Going back home.

22-NEST

MORNING

Bench

with soap and towel. Fire. Mamma makes breakfast.

23-Mama

in the kitchen. We are eating by the table. Clock.

24-MAMMA’S

WORK NEVER END

Taking

apples into the barn. Washing the pail.

25-BROTHER

PETRAS ARRIVAS (ECONOMIST AT THE COLLECTIVE FARM)

We

walk about the birches. At the cemetaries.

26-

Horses behind the river. Rusting pails. Adolfas by the river. Stork.

27-OUR

OLD TOILET IS STILL THERE

28-Mama

comes with a stool. Sits and eats berries. The red berry bush.

29-BROTHER

KOSTAS ARRIVES (IN CHARGE OF GRANERY AT THE COLLECTIVE FARM VIENYBE)

30-MAMMA

PREPARES RUTA (RUE) SEEDS

31-IN

THE FIELD OF COLLECTIVE FARM VIENYBE MY OLD SCHOOL FRIEND JONAS DRIVES THE

COMBINE

Jonas.

Grain. Boy in the grain.

32-Woman

by the table. Eating and drinking.

(Reel

2)

33-THE

RITUAL OF MEASURING THE HEIGHT

34-BROTHER

POVILAS ARRIVES (VETERINARIAN AT GAIDZIUNAI)

35-OUR

SISTER ALZBUNE WHO DOESN’T FEEL WELL

36-Motorcycle

scene.

37-Fooling

around with the camera.

38-WHEN

MORE THAN ONE LITHUANIAN GET TOGETHER THEY SING

Singing.

39-Dancing.

40-Washing

faces

41-Dancing

at Petras’. Accordion. Singing. Hay.

42-NEXT

MORNING AT PETRAS’ PLACE

Washing

by the well. Petras cleans the house.

43-Drinking

beer by the house, watching the road, horses pulling wagon, women drink beer.

Petras sits on the stone.

44-The

whole crowd outside by the house. I am being offered a glass of beer.

45-Children

orchestra.

46-Digging

for potatoes.

47-Povilas

and Petras drink beer. Peeling of potatoes. The pail comes out of the well.

48-Children

playing with the barn door.

49-Our

nephew watches flowers. Women by the well. Flower on the fence. Mother talking

with a friend. Apples in wind.

50-RECEPTION

AT COLLECTIVE FARM VIENYBE

Begin

music.

51-THE

OFFICE OF THE COLLECTIVE FARM

52-Mama

scaptically watches Pola. Mama watches her face.

53-IN

THE MORNING

Breakfast

54-Parenthesis.

The Castle.

55-By

the lake.

56-

“ “

“

57-

Visiting the neighbor. Neighbor arrives on bike. Offers beer.

58-

Driving to Brother Kostas. Our birth spot.

59-Driving.

60-Sheep.

61-Petras dunks goose.

62-Petras mows.

63-Apples, walking into the house, hens pecking apples.

64-THE

HOUSE OF BROTHER KOSTAS

Front

door of Kostas’ house.

65-

In the kitchen. Goose pecking apples.

66-

By the table.

67-

Kostas standing. Petras comes with women. Adolfas mows.

68-

Kostas’ family portrait.

69-

Kostas plays with wheelbarrow.

70- They make me pull the plow

71- Petros and Kostas by the

flowers.

72- Our old schoolhouse

73- Light

athletics.

74- We go to see how they milk cows.

75-

Petras make a flute.

76-

Mama alone by the table. The goose.

77-Mama

walking home. The bridge. Petras’ family leaves. Mama walks down the empty

road.

78-WE

NOTICE A MOOSE DRINKING AT THE RIVER

Boy

plays with red house.

79- We go again to the neighbor for milK

80-MAMMA

MAKES FIRE

Cat

walks around.

81-

Side of the house. Myself mowing. Petras joins in. We go home singing. Mama by

the pots. Mama tastes soup.

82-

Mother with basket of apples.

83-

Petras’ wife gathers flowers from the field. More flowers. Apples on the

ground. Mama sits by the well and eats alone.

84-MAMMA

BAKES POTATO PANKAKES

Pancakes.

Bath house. I bring wood.

85-In

the cemetaries.

86-Mother

runs home. Birds over the fields.

87-MAMMA

IN KAUNAS

88-

My feet. Mama with flowers.

89-THE

FAMILY OF OUR COUSIN POVILAS (COMPUTER ENGINEER)

90-

Boys fishing.

91-

Rain. Departure. Legs.

PART

THREE

PARENTHESIS

Square

IN

ELMSHORN, A SUBURB OF HAMBURG

Adolfas

lying on the ground.

GERBRUDER

NEUNERT FACTORY IS STILL THERE

Factory.

In the street.

PARENTHESIS

CLOSED

In

Vienna. Kubelka. Peter feeds birds. The waiter comes. Birds on Peter’s palm.

At Cafe Konstantinhugel.

THE

WINE CELLARS OF PROF. MIKUTA

The

wine-seller

THE

HOUSE OF WITTGENSTEIN

ST. HERMANN NITSCH ACQUIRES A CASTLE FOR HIS THEATRE

ST.

ANNETTE

Hermann’s

castle.

Peter’s

house party.

Annette

in the street. Nitsch.

Ken

Jacobs arrives. In the cafeteria. Hermann walks away.

Ken

Jacobs with binoculars. Demel.

Ken

Jacobs with Niese.

A

VISIT TO MONASTER AT KREMSMUNSTER

The

wedding.

Annette.

Peter picking apples. By the table. Peter shows Niese how to shake an apple

tree. Soup is served. Peter eats fish.

THE

WEDDING PARTY DANCED LATE INTO THE NIGHT

Display

of bishops’ vestements.

Peter

“the bishop”.

The

library. Peter sings.

Drinking

water.

Fish

pond. Wedding party.

View

from the roof of the Observatory. Train. Close-up of Peter. Footbool players.

Austrian flag. Clouds. Peter conducts.

LATE

AT NIGHT, ON OUR WAY BACK, WE SAW VIENNA BURNING

THE

END OF REMINISCENCES

by

Jonas Mekas

1971.[5]

La

complessa struttura temporale di questo film costituisce “a dialectical

meditation on the meaning of exile, return, and art”. Essa si compone di bellissime immagini e altrettante semplici

e malinconiche parole, commentate fuori campo dalla voce dello stesso

film-maker.

La

prima parte di Reminiscences si apre con una serie di inquadrature girate nel

1957, o 1958, in una foresta, che rappresentano metaforicamente la fine di quel

periodo vissuto dall’autore come uno sradicamento dalla terra nativa.

“That

early fall, in 1957 or ’58, one Sunday morning, we went into the Catskill,

into the woods. We walked through the leaves, beating the leaves with a stick.

We walked up and up, deeper and deeper. It was good to walk like that and not to

think, not to think anything about the last ten years and I was wondering myself

that I could walk like this and not to think about the years of war, of hunger

of Brooklyn. And maybe it was for the first time as we were walking through the

woods that early fall day, for the the first time, I did not feel alone in

America. I felt the ground, the earth, leaves and trees anf people. And like I

was slowly becoming a part of it. For a moment I forgot my home. This was the

beginning of my new home. “Hey! I escaped the ropes of time once more”, I

said.”[6]

Dopo

queste prime immagini di riconciliazione, che annunciano la fine di un esilio

(rappresentato precedentemente da Walden),

Mekas torna indietro al 1950, con una serie di sequenze che

descrivono da una parte la personale esperienza dei due fratelli , di

come si sentissero soli e diversi dal resto degli immigrati,

“I

walk trough the streets of Brooklyn, but the memories, the smells, the sound

that I was remembering were not from Brooklyn.

They

used to have their picnics, at the and of Atlant Avenue, in Brooklyn, the old

immigrant, and the new. And when I look at them, they looked to me like some

strange, dying animals, in a place they didn’t belong to, in a place they

didn’t recognice. They were there, on the Atlantic Avenue, but they were

completely somewhere else.”

“Some

footage I took with my Bolex. I wanted to make a film against war. I wanted to

shout that there was a war because I walked the street and I thought that nobody

knew that there was a war; that there were homes in the world where people could

not sleep; where the doors are being kicked in at night with the boots of

soldiers and police, where I came from. But in this city nobody knew that.”[7]

e

dall’altra descrivono invece, con un accorato ricordo, quelle numerose

Displaced Person che come loro avevano perso tutto,

“Yes,

I remember you, my friends from the Displaced Person camp, from the miserable

post-war years. Yes, we are, we still are Displaced Person even today and the

world is full of us. Every continent is full of displeced persons. The minute we

left, we started going home and we are still going home. I am still on my

journey home. We loved you, world, but you did lousy things to us!”[8]

e,

come loro, si trovavano ora a dover ricominciare in un nuovo mondo.

“Have

you ever stood in Time Square and suddenly felt very close to you and very

strong, the smell of a fresh bark fo a birch tree?”

“My

brother said he was a pacifist and that he hated war. So they drafted him into

the army and they took him to Europe, back to all the war memories. So he

started eating leaves from the trees and they thought he was crazy. So they

shipped him back to the States.”[9]

Nella

seconda parte la struttura è simile alla prima: la visita alla madre e alla

terra nativa rappresentano la celebrazione di un ritorno al passato, un cammino

all’indietro nel tempo e nei posti dove l’autore viveva prima del 1950.

Essa

è caratterizzata da “100 glimpses” (in realtà Mekas ne tagliò alcuni e

terminò al novantunesimo) che raccontano, momento per momento, l’intero

viaggio in Lituania, dall’arrivo in auto al paese nativo, all’incontro con

la madre:

“And

there was Mamma and she was waiting. She was waiting for 25 years. And there was

our uncle who told us to go west. “Go children, west and see the world!” And

we went and we are still going.”

“The

berries, always berries, uogos, the berries.”

“We

had to see our uncle’s church. Our uncle is a reformed Protestant pastor and a

very wise man. He was a friend of Spengler and he has all his books there _maybe

that is why he told us to go west...The house, the attic in which I lived in the

years of my studies, I had a rope dangling to slide down in case the Germans

came and banged at the door."

“And

as we were approaching closer and closer to the places we knew so well,

suddenly, in front of us we saw a forest. I did not recognize the place. There

were no trees when we left; we planted small seedling all around, yes. And now

little seedlings had grown up into big, large trees.”

“Our

home, our house was stll there and the cat met us.

So

what does one do first when one comes home? Of corse, we went to the well to

drink some water. Water that tasted like no other water. Cool water of

Semeniskiai! No wine tasted better anywhere.”

“Mamma

complaining that her memory is failing. She can’t find her spoons. She has

ten, and she can not find a single one this morning. “The only thing to know

about old age is that when you get old you cannot find your spoons”, she

said.”[10]

Dall’incontro

con i fratelli e con gli amici di un tempo,

“Brother

Petras arrives. We talk about the trees; how tall they have become.”

“We

decided to go to the fields to see how the work is done these days and Petras

leads us and he is very excited. He wants to show us everuthing. And there, high

on the combine sits Jonas Ruplenas with whom I went to school together. We used

to take care of cows and sleep in the fields, and there he sits, now, and he is

so big and the machine is so big and the fields are so wide. Brother Kostas

sings a song about the collective farm work. We all join in.”

“Oh

these personal ramblings! Of course, you would I like to know something about

the social realities. How is the life going in the Soviet Lithuania? But what do

I know about it! I am a displaced

person on my way home, in search of my home, retracing bits of memories, looking

for some recognizable traces of my past. The time in Semeniskiai remained

suspended for me, remained suspended until my return. Now, slowly, it is

beginning to move again.”

“Later,

we all go to Petras’ place and so it goes, late into the night.”

“When

we had enough, when we had enough of it, brother Petras brought some hay from

the barn and there we slept. In the morning, brother Petras took the hay back to

the barn. He was sort of hiding. He said, “Don’t tell them there in America

that we sleep in hay”. He thought it was funny.”

“That

evening the collective farm Vienybe (which means togetherness) gave us a

reception. A collective farm consist of a dozen former villages.”

“Our

mother is telling us about the terrible post-war times. How the police were

waiting for a years for me to come home, because they thought I joined the

partisans. Every night the police were waiting behind the house in the bushes

for me to come home and the dogs used to bark and bark.[11]

ai

ricordi di gioventù:

“But

I was young and naive and patriotic and I was editing this underground newspaper

directed against Nazi occupation and I had this typewriter I was hiding in a

stack of wood, outside by the house. And a thief, one night, snooping for

something, found it and stole it and it was only a question of days or hours

when the Germans would catch him. I had very little time to disappear and at

this moment that our wise uncle told us, “Go children, west. See the world and

come back”. False papers were made for us to go to the University of Vienna to

study there, and there we went. The only thing was that we never got there.

German soldiers directed our train to Hamburg. We ended up in the slave camps of

Nazi Germany.”[12]

Dai

momenti più intimamente famigliari,

“We

goofed around and even Kostas came home early from his grainery. We walk around

the houses; we touched some of the things we used to work with. Of course, they

are not any more in the fields, but it is memories for us. As we mow the grass

around the houses, it was reality only as a memory.

But

the fence in the junkyard, we found an old plow. It is not used now, and brother

Kostas said to me, “Ok, now pull it!”, and he was beating me. “Now you

film this to show to the Americans how miserably we live. That is what they want

to see and that is what you should give them!” Of course, he thought it was

very funny.”

“We

decided to go to see our old schoolhouse. We all went to the same school. Long,

deep, cold winters through the fields, through the rivers, through the forests

we walked to the school with our noses frozen, our faces burning in the cold

wind and snow. But ah, those were beautiful days. Those were winters I will

never forget. Where are you now, my old childhood friends? How many of you are

alive? Where are you, scattered through the graveyards, through the torture

rooms, through the prisons, through the labor camps of the western civilization!

But I see your faces just like used to be. They never change in my memory. They

remain young. It is me who is getting older.”

“This

is a new song. It is about somebody who is far away and he says, “Oh, mother,

how I would like to see you again. I hope the long, grey road will lead me home,

will lead me soon home again.””

“This

morning the fire was slow to start. Our mother cooks outside. He doesn’t like

to cook indoors. It is too hot and too smoky. She likes outdoors. And the fire

just did not want to come this morning. So, she gathered some old branches and

some leaves and some newspapers and kept blowing at it, and I blew at it. It

took a very, very long time, but finally we got it going.”

“Yes,

they were waiting for you every night for more than a year, behind the bath

house. The dogs used to bark and bark every night.”

“The

women of my village that I remember from my childhood, they always remaind me of

the birds, sad, autumn birds as they fly over the fields crying sadly. You led

hard and sad lives, women of my childhood.”[13]

al

giorno della partenza:

“The

day I was leaving it was raining. The airport was wet. It was sad. It was funny:

I was looking at the legs of a stewardess. I remembered, it was my old friend

Narbutas who said, “As long as a man is looking women’s legs, he should not

marry”. So I guess I won’t marry soon.”[14]

In

questa seconda parte l’elogiaco tono iniziale, accentuato dall’uso del

montaggio e del commento sonoro di Mekas, scompare nell’ode di mezzo, che si

presenta come una pura accettazione dell’impossibilità di un ritorno in quei

luoghi e ai tempi della propria giovinezza.

La

terza parte è dedicata invece al riconciliarsi di Mekas con la sua “American

cultural family”: “culture, as represented by Kubelka, Jacobs, Annette,

Nitsch, and become my home. It was clear already at that time that there was no

going back to Lithuania for me.”

Qui

l’autore risolve le contraddizioni espresse nelle due parti precedenti,

salutando definitivamente il proprio passato, e celebrano il presente con

rinnovato vigore:

“In

Elmshorn, Adolfas is lying exactly on the spot where our bed used to be in the

labor camp. When we asked some poeple around, nobody remembered that there was a

labor camp there. Only the grass remembers.”

“One

of the factories, the Gebruder Neunert, where they used to take us to work,

together with French, Russian and Italian war prisoners, is still there. There

is bench where I used to work, where I was beaten up for working too slow and

talking back. The foreman recognized Adolfas. They spoke about this and that. He

was a young and good foreman. In March ‘45,

we escaped and ran Denmark and we were caught near the border of Danmark and

when they were shipping us back, we excaped once more and for the last three

months of war we hid ourselves in Schleswig-Holstein on a farm.”

“Outside,

as my brother was looking and remembering, there were children around. They

thought it was very funny, these strange poeple coming to see, standing here.

They thought it was really funny. Auslander.

Oh

yes, run children, run. I was also running once from here, but I was running for

my life. I hope you will never have to run for your life. So, run children,

run.”[15]

e

celebrando il presente, affermando la propria rinascita come artista.

“I

was watching Peter and I caught myself envying him, his peace, his serenity, his

being just in himself, with things around him, with things that he had always

been with, at home, in peace, in time, in mind, in culture.”

“Annette,

she walks through New York and Vienna with the same optimism and courage. I

admire her. I admire Annette, for making culture into the roots, into her

life.”

“And

there is Hermann Nitsch, pursuing his vision, without giving in an inch, and

heroically. And Ken Jacobs, who has the courage to remain a child in the purity

of his seeing and his ecstasies.”

“No,

I never got to Vienna that time. But strange circumstances pulled me back. And

there I am now, here. And so as I walk through Vienna, with Peter, and as we

talk, as we go through the galleries, through the monasteries, and Dehmel:

through the wine cellars and through the wine groves, _I begin to believe again

in the indestuctability of the human spirit; in certain qualities, in certain

standards that have been estabilished by man through many thousands of years and

they will be here when we are gone.”

“We

stood there that August evening in Kremsmunter, a few friends, on the roof of a

1200 year old monastery and the evening was coming, the sun was setting; a blue

light was falling over the landscape. It was very, very peaceful. Our hearts and

our minds elated.”

“On

our way back home to Vienna, from far away, we saw a fire. Vienna was burning!

The fruit market was on fire. Peter sais it was a pity. He said it was the most

beautiful market in Vienna. He said the city probably set it in fire to get rid

of it. They want a modern market now.”[16]

Sebbene

le riprese siano assai esplicite nella loro descrizione consequenziale degli

avvenimenti, grande parte del merito della bellezza di questo film si deve

attribuire alla sezione sonora. Attraverso le parole di Mekas, infatti, le tre

parti di cui si compone il film si uniscono in un unico resoconto intimista e

poetico, attribuendo all’opera una forma ancora più personale. Tutto ciò è

infine accompagnato da un’accurata colonna sonora composta da alcune canzoni

folcloristiche lituane, cantate anche dagli stessi fratelli Mekas.

“I

decided later, after the filming, whatever sound I used. I collect the sound

whenever I can. Usually I end up with certain footage, and certain sounds

surrounding the same situation. I look at my footage as memories and notes, the

same way I look at my sound, collected during the same period. In the case of

the music for the Lithuania part of Reminiscences, it’s just a coincidence

that I received a record that I had admired very much. It’s music written

around 1910 by a young Lithuanian composer-painter, Ciurlionis, who died very

young in the insane asylum. I recorded certain passages over and over, some

parts of it. There may be influences of Scriabin in it (that what some have

said) but essentialy it is Lithanian music. There are certain notes in it that

speak to me and I listen to it all the time until the record was stolen from me

together with the photograph about ten years ago. So that this music means

something to me, is very close to me, and that’s why I used it. I used it like

a loop, in a sense. I thought it will help me to join all the disperate pieces

together, by means of this sound loop. I used Bruckner for the Kubelka sequence

in Vienna because Bruckner happened to be one of Kubelka’s favorite composers.

The madrigal I used in the Kremsmuenster library was one of Kubelka’s favorite

madrigals. So it’s all very personal”[17]

Oltre

alla suddetta tripartizione, Reminiscences

si compone attraverso l’uso di ripetuti schermi neri che dividono in

paragrafi le varie scene, nella prima e seconda sequenza (la terza è scandita

invece dai 91 glimpses), e di titoli che servono allo spettatore per conoscere,

in precedenza ciò che stanno per vedere (“I like to tell in advance what it

is, what’s coming, as much as I can”).

Per

quanto riguarda il montaggio totale dell’opera,

“...

in the case of Reminiscences, the

editing was very fast. Hans Brecht of Norddeutcscher Television helped me to pay

for the film stock and Bolex in return for the rights to show it on German

television. But then I came back, and I completely forgot about Hans Brecht. And

he forgot abouut me. But then, on Christmas day he called me. “Is it ready? I

need it on January twentieth.” “Jannuary twentieth? Why didn’t you tell me

this earlier?” I went to my editing table and I started at it. After I came

back from Lithania, I kept thinking: “How am I going to edit it?” This

footage was very very close to me. I had no perspective to it of any kind. And

even now, today, I have little perspective to it. I had about twice as much

footage as you see in the film. So now I stood there and I said to myself:

“Fine, very fine. This emergency will help me to make decision.” For two or

three days I didn’t touch the footage, I thought about the form, the structure

of the film. Once I decided upon the structure, I just spliced it, very fast, in

one day. I knew that this was the only way I could come to grips with this

footage: by working with it totally mechanically. Another way would have been to

work very very long on it, and either to come up with a completely different

film, or destroy the footage in the process.”[18]

Lo

stile di ripresa adottato da Mekas in questo film si discosta nettamente, almeno

nella parte girata nel 1971, dal precedente utilizzato in Walden. Come racconta

lo stesso film-maker, nel momento di partire per la Lituania egli era convinto

che avrebbe riportato materiale girato con la tecnica dei single frame,

“but,

somehow, when I was there, I just couldn’t work in the style of Walden, there.

The longer I stayed in Lithuania the more it changed me, and it pulled me into a

completely different style. There were feeling, states, faces that I couldn’t

treat too abstractly. Certain realities can be presented in cinema only through

certain durations of images. Each subject, each reality, each emotion affects

the style in which you film. The style that I used in Reminiscences wasn’t the

most perfect style for it. It is a compromise style.”[19]

Un

altro fatto che compromise lo stile registico di Mekas fu dovuto all’utilizzo

per girare queste scene di una nuovissima Bolex, mai usata prima. Come spiegherà

poi lo stesso Mekas ogni cinepresa è differente da un’altra e quindi solo

quando egli si trovò a dover girare,

si rese conto dei suoi difetti:

“It

was, actually, defective, never kept a constant speed. I set in on 24 frames,

and after three or four shot it’s on 32 frames. You have constantly to look at

the speed meter, because the speeds of frames per second affect the lighting,

exposure. And when I finally realized that there was no way of fixing it or

locking it _I decided to accept it and incorporate the defect as one of the

stylistic devices, to use the changes of light as structural means.”[20]

Reminiscences

of a Journey to Lithuania

ebbe la sua prima ed importante proiezione nel Novembre del 1972 al New York

Film Festival, gareggiando in concorso con il film

Going Home, diretto da Adolfas

Mekas.

Entrambi

i film non fecero una buona impressione al pubblico di giornalisti e critici:

Kevin M. Saviola per esempio a proposito dell’andare al cinema a vedere o no i

film dei due fratelli Mekas, consigliava di andarci solo in caso si fosse loro

parenti, altrimenti di declinare doverosamente l’invito.

In

una recensione del Daily News invece il critico affermava:

“and

it is the ultimate home movie, full of flashes and bad exposure and epiletic

camera movements that forced me to close my eyes from time to time to avert

nausea. (...) the welter of images overwhelms emotion and leaves one exhausted

and annoyed.”[21]

La

recensione di Variety lo definiva

“dull, repetitious, poorly photographed “home movie”....”

“The

technical aspects of the jointed cinematic visit are so bad, choppy editing,

over-exposed shots, abrupt editing and repeated versions of the same scenes,

plus the fact that nothing really happens, result in a dull effort that leads to

the conclusion that its selection

for the fest was made sight unseen.”[22]

Jonathan

Rosenbaum che scriveva sul Village Voice

se sentì in dovere di difendere il proprio collega, e denunciò il fatto,

incolpando la critica di aver ridotto queste opere in “a casual victim of

‘convenient’ programming and somewhat deceptive labels”.[23]

La

recensione di Vincent Canby del New York

Time fu invece nel suo complesso positiva:

“The

program makes for an evening rather more brimful of Makases than one might

ordinarily seek out, yet it’s also successively moving, indulgent, beautiful,

poetic, banal, repetitious and bravely, heedlessly personal. Although

‘Reminiscences’ can stand by itself well enogh, it is a continuation of the

‘Diaries’ in style and mood. (...) Although I’m told that neither brother

was allowed to see the other’s film until it was completed, Adolfas’s

‘Going Home’ serves as a rather homey (a little too homey, I’m afraid)

curtain-raiser to Jonas’s film. (...) ‘Reminiscences’ is an especially

appealing film, and a good deal more than a record of Jonas Mekas’s summer

vacation. It is a testament to all person displaced, geographically, as the

Mekas brother were, and spiritually.”[24]

come

quella di Anthony Bannon sul Buffalo

Evening News :

“Reminiscences

of a Journey to Lithuania” a new

film by Jonas Mekas, is a touching work of purification and nourishment, a film

diary of a man’s return to fatherland after a 25-years forced absence,

presented with the kineticism of impulse which allows one to see it without the

embarassment of sentimentality.”[25]

e

di Mauritz Edstrom sul Dagens Nyherter

(rivista svedese):

“Jonas

Mekas film ar en intensiv investering av en manniskas barndomslandskap, dar alla

avgorande impulser gavs. Minnena son overlevt kanslans landsflykt lendsagar

bilderna genom den konkreta, sensuellt doftrika men aldrig sentimentala texten.

(...) ‘Minner av en resa till Litauen’ har ingenting av den konventionella

tekniska perfektion som filmer vanligen prisas for. Men den har nagot battre: en

levande andning. Der hor till de filmer son kan fa oss att fa lust pa mer

film.”[26]

[1] Mac Donald, S., “Interview with Jonas Mekas” op. cit., pag. 111.

Traduzione: “Improvvisamente sentii che avevo abbastanza possibilità di ricevere un lasciapassare per visitare la Lituania. Da quando fui invitato al festival di Mosca avevo pensato di chiedere il permesso di andare anche in Lituania as visitare mia madre. Per circa dieci anni mi era stato negato il persino di scriverle. Avevo scritto alcune poesie contro Stalin così ero un criminale. I miei fratelli erano stati arrestati a causa mia e mio padre era morto prematuramente a causa di ciò. La casa di mia madre era stata tenuta sotto sorveglianza per anni dalla polizia segreta. Speravano che un giorno sarei tornato a casa. Mia madre mi raccontò questo nel 1971. Non ci fu una notte durante la mia visita che non fossi preparato a saltare fuori dalla finestra e scappare dalla polizia se avessero deciso di venire a prendermi. E questo nel 1971, molti anni dopo la morte di Stalin.”

[2] Ibidem.

Traduzione: “Improvvisamente potevo filmare ovunque. Di solito i visitatori non possono uscire dal villaggio; essi stanno intorno agli alberghi. Mi fu offerto una trup ufficiale da usare dove volevo, ma io dissi: userò la mia Bolex, non voglio nessuna trup. Essi lo trovarono strano ma me la diedero lo stesso. Essi mi stettero intorno per la maggior parte del tempo girando il loro film su di me e mia madre _in cinemascope. Mi mandarono una copia, che ho ancora. Io stesso girai alcune riprese anche a Mosca in quel viaggio, ma non le ho usate.”

[3] Sitney, P. Adams, Visionary Film op. cit., pag. 363.

Traduzione:

“Egli usa questo viaggio di ritorno

in patria dopo venticinque anni per costruire una meditazione dialettica sul

significato di esilio, ritorno e arte.”

[4] Materiale originale, fornito dall’autore.

[5] Materiale originale del film, fornitoci da Jonas Mekas

[6] Tratto dal sonoro originale.

Traduzione: “Questo accadde nel 1957 o 1958, una domenica mattina, noi andammo a Catskill nella foresta. Camminammo tra i rami, battendoli con un bastone. Camminammo e camminammo sempre più in profondità. Era bello camminare così senza pensare senza pensare a nulla che era accaduto negli ultimi dieci anni e speravo di poter camminare così senza pensare agli anni della guerra e della fame di Brooklyn. E forse fu per la prima volta mentre camminavo così nella foresta, fu per la prima volta che non mi sentii più solo in America. Sentivo il terreno, la terra, i rami gli alberi e le persone. Come se stessi diventando parte di essa. Per un momento dimenticai la mia casa. Questa era l’inizio della mia nuova casa: Sì! Sono riuscito ancora una volta a sciogliere i nodi del tempo, dissi.”

[7] Ibidem.

Traduzione:

“Cammino tra le strade di Brooklyn

ma i ricordi gli odori e i rumori che stavo ricordando non erano di

Brooklyn.

Essi

erano soliti avere i loro picnic alla fine di Atlant Avenue, a Brooklyn, i

vecchi immigranti e i nuovi. E quando li guardavo essi mi guardavano come

strani animali moribondi, in un posto a cui non appartenevano in un luogo

che non riconoscevano. Essi erano lì in Atlantic Avenue ma erano

completamente in un altro posto.

Alcune riprese fatte con la mia Bolex. Volevo fare un film contro la guerra. Volevo gridare che c’era una guerra perché attraversavo le strade e pensavo che nessuno sapeva che ci fosse una guerra; che c’erano case nel mondo in cui le persone non potevano dormire; c’erano porte che erano state buttate giù dai soldati e dalla polizia, da dove venivo io. Ma in questa città nessuno lo sapeva.”

[8] Ibidem.

Traduzione: “Sì ti ricordo amico dei campi per Displaced Person, dei miserabili anni del dopo guerra. Sì siamo ancora Displeced Person anche oggi ed il mondo è pieno di noi. Ogni continente è pieno di Displaced Person. I minuti che abbiamo perso, abbiamo iniziato a tornare a casa e stiamo ancora cercando di tornare a casa. Io sono ancora in viaggio per la mia casa. Noi ti amiamo mondo ma tu ci hai fatto del male.”

[9] Ibidem.

Traduzione:

“Sei mai stato in Time Square e

improvvisamente hai sentito vicino e forte l’odore di una corteccia fresca

o di un albero di betulla?

Mio fratello disse che era un pacifista e che odiava la guerra. Così lo gettarono nell’esercito e lo riportarono in Europa, indietro verso i ricordi della guerra. Così egli iniziò a mangiare foglie dagli alberi e loro pensarono che fosse pazzo. Così lo rispedirono in America.”

[10] Ibidem.

Traduzione:

“E lì c’era la mamma e ella stava

aspettando. Ella stava aspettando da venticinque anni. E lì c’era nostro

zio quello che ci aveva detto di andare all’ovest. “Andate ragazzi

all’ovest e vedete il mondo!” E noi andammo e siamo ancora in cammino.

Bacche

ovunque bacche e ancora bacche.

Dovevamo

visitare la chiesa di nostro zio. Nostro zio è un prete protestante ed un

uomo molto saggio. Egli era un amico di Spengler e possedeva tutti i suoi

libri _forse è per questo che ci disse di andare all’ovest... La casa,

l’attico nel quale vissi negli anni dei miei studi. Avevo un foro per

scappare nel caso in cui i Tedeschi fossero venuti e avessero sbarrato la

porta.

Non

appena fummo sempre più circondati dai luoghi che tanto conoscevamo bene,

improvvisamente di fronte a noi trovammo una foresta. Non riconoscevo più

quel posto. Non c’erano alberi quando ce n’eravamo andati; avevamo

piantato piccoli alberi li intorno, sì. E ora quei piccoli fuscelli erano

cresciti in grossi e larghi alberi.

La

nostra casa, la nostra casa era ancora lì ed il gatto ci riconobbe.

Così

cosa fa uno quando torna a casa? Certamente andammo al pozzo a bere

dell’acqua. Acqua che sapeva come nessuna altra acqua al mondo. Fresca

acqua di Seminiskiai! Nessun vino è migliore ovunque.

La mamma sta capendo che la sua memoria inizia ad avere dei problemi. Ella non riesce a trovare i cucchiai. Ne possiede dieci e non ne riesce a trovare uno questa mattina. “L’unica cosa da sapere circa l’età avanzata è che quando invecchi non puoi più trovare i tuoi cucchiai” disse. “

[11] Ibidem.

Traduzione:

“E’ arrivato mio fratello Petras.

Egli cammina tra gli alberi; come sono diventati alti.

Decidemmo

di andare nei campi per vedere come si lavora oggi e Petras ci guida

eccitato. Egli vuole mostrarci tutto. E lì in alto sul trattore sta Jonas

Ruplenas con il quale andai a scuola. Eravamo soliti guardare le mucche e le

pecore nei campi, e adesso lui siede lì, ed è così grosso e la macchina

è così grossa e i campi così immensi. Mio fratello Kostas canta una

canzone che riguarda il lavoro della cooperativa. Partecipiamo tutti.

Oh

questi vagabondaggi personali! Certamente avreste voluto sapere qualcosa

circa le realtà sociali. Come va la vita nella Lituania sovietica? Ma cosa

ne posso sapere io! Sono un deportato sulla strada per casa, in cerca della

mia casa, in cerca di piccoli ricordi in cerca di qualche traccia del mio

passato. Il tempo a Semiskiai è rimasto sospeso per me, e lo è rimasto

fino al mio ritorno. Ora lentamente esso sta ricominciando a scorrere di

nuovo.

Più

tardi andammo tutti da Petras e li stemmo fino a notte fonda.

Quando

ne avemmo abbastanza nostro fratello Petras ci portò della paglia dalla

stalla e sopra a questo dormimmo. Al mattino nostro Petras riportò la

paglia nella stalla. Egli ci disse, “Non dite la in America che dormiamo

sulla paglia.” Egli pensava che ciò fosse ridicolo.

Quella

sera la cooperativa Vienybe, che significa stare assieme, ci diede udienza.

Una cooperatriva agricola consiste in una dozzina di capi villaggio.

Nostra madre ci sta raccontando del terribile periodo del dopo guerra. Di come la polizia aveva aspettato per anni che io tornassi a casa, perché pensavano facessi parte dei partigiani. Ogni notte la polizia mi aspettava dietro la casa nei cespugli e i loro cani abbaiavano tutta la notte.”

[12] Ibidem.

Traduzione: “Ma io ero giovane e naive e patriottico e stavo scrivendo un giornale underground contro l’occupazione nazista e avevo questa macchina da scrivere che avevo nascosto in un tronco, fuori casa. Poi arrivò un ladro una notte e cercando qualcosa la trovò e la rubò e così sarebbe stata solo una questione di giorni o ore e i tedeschi mi avrebbero preso. Avevo poco tempo per sparire e fu in quel momento che il nostro saggio zio ci disse “Andate all’ovest ragazzi. Guardate il mondo e tornate”. Carte false furono fatte perché noi potessimo andare all’università di Vienna a studiare, e li ci dirigemmo. L’unica cosa sicura fu che non vi arrivammo mai. I soldati tedeschi diressero il treno ad Amburgo. Noi finimmo il nostro viaggio in un campo di lavoro della Germania nazista.”

[13] Ibidem.

Traduzione:

“Gironzolammo in giro e anche Kostas

venne a casa presto dal suo lavoro. Girammo intorno alla casa; vedemmo

alcune delle cose che usavamo per lavorare. Certamente esse non si usano più

nei campi ma sono per noi dei ricordi. Non appena attraversammo il giardino

di casa la realtà si mischiò con i ricordi.

Poi

trovammo un aratro. Adesso non è più usato, e Kostas ci disse, “Avanti

tiralo su!, e mi picchiava, “Adesso filma questo per mostrare agli

americani in che modo miserabile viviamo. Questo è ciò che vogliono vedere

e questo è ciò che dobbiamo dargli.!”. Certamente egli pensava che ciò

fosse divertente.

Decidemmo

di andare a visitare la nostra vecchia scuola. Andavamo tutti nella stessa

scuola. Lunghi freddi e profondi inverni attraverso i campi tra i fiumi e le

foreste andavamo a scuola con i nostri nasi freddi e le nostre facce

brucianti nel freddo vento e nella neve. Ma quelli sì che erano bei giorni.

Quelli erano inverni che non dimenticherò mai. Dove siete adesso amici di

gioventù? Quanti di voi sono ancora vivi? Dove siete, sbattuti in

sotterranei, nelle stanze di tortura nelle prigioni nei campi di lavoro del

ovest civilizzato. Ma vedo le vostre facce come lo erano un tempo. Esse non

cambieranno mai nella mia memoria. Essi rimangono giovani. Sono io che

divento più vecchio.

Questa

è una canzone nuova. Essa parla di qualcuno che è lontano e dice “O

madre come vorrei rivederti ancora. Spero che la lunga grigia strada mi

porterà a casa presto ancora.”

Questa

mattina il fuoco era lento ad accendersi. E’ troppo caldo e fumoso. A lei

piace stare fuori. E il fuoco non vuole accendersi questa mattina. Così

ella prende alcune pezzi di legno e alcuni giornali e ci soffia sopra, e

anche io ci soffio. Ci volle molto tempo ma alla fine ci riuscimmo a farlo

andare.

Sì,

essi ti aspettarono tutte le notti per più di un anno dietro la casa tra i

cespugli. I cani abbaiavano tutta la notte.

Le donne del mio villaggio che ricordo dalla mia fanciullezza esse mi riportano agli uccelli, quei tristi uccelli d’autunno che volavano sui campi urlando tristemente. Esse vivevano una vita difficile e triste, le donne della mia fanciullezza.”

[14] Ibidem.

Traduzione: “Il giorno in cui me ne andai pioveva. L’aeroporto era bagnato. Ciò era triste. Era divertente: io stavo guardando le gambe delle hostess. Ricordai le parole che mi disse un amico, “Quanto a lungo un uomo guarda le gambe delle donne, egli non si sposerà”. Così speravo che non mi sarei sposato presto.”

[15] Ibidem.

Traduzione:

Traduzione: “In Elmshorn, Adolfas

era sdraiato esattamente nel posto dove era i nostri letti nel campo di

lavoro. Quando chiedemmo ad alcune persone nessuno si ricordava che quello

era stato un campo di lavoro. Solo il terreno ricordava.

Una

delle fabbriche dove ci portavano a lavorare insieme ai francesi ai russi e

agli italiani è ancora lì. C’è una panca adesso dove lavoravo io, dove

ero solito essere picchiato perché andavo troppo lento e rispondevo. Il

caposquadra riconobbe Adolfas. Essi parlarono dei più e del meno. Egli era

un bravo e giovane capo. Nel Marzo del ’45 noi scappammo e andammo in

Danimarca e fummo ripresi vicino il

confine e quando ci rispedirono indietro scappammo di nuovo per gli ultimi

tre mesi di guerra e ci nascondemmo in una fattoria a Schleswing-Holstein.

Fuori

mentre mio fratello guardava e ricordava, c’erano dei ragazzini. Essi

pensavano fosse divertente vedere

queste strane persone venute a visitare quel luogo che stavano li in piedi.

Pensavano fosse veramente divertente.

Sì correte ragazzi correte. Anche io una volta corsi via da qui, ma correvo per la vita. Spero che voi non dobbiate mai correre per la vita. Così correte pure ragazzi, correte.”

[16]

Ibidem. “Stavo guardando Peter e mi

scoprii ad invidiarlo, per la sua pace, la sua serenità per il suo essere

solo in se stesso, con cose che lo circondano, con le cose con cui è sempre

stato, a casa in pace nel tempo, nella mente, e nella cultura.

Annette,

ella cammina per le strade di New York e Vienna con lo stesso ottimismo e

coraggio. Io la ammiro. Io ammiro Annette per essere riuscita a creare la

cultura alle sue radici, nella sua vita.

E

c’è Nitsch che persegue la sua visione, senza darci qualcosa ed

ironicamente. E poi c’è Ken Jacobs che ha il coraggio di rimanere un

fanciullo nella purezza della sua visione e delle sue estasi.

No

non andai mai a Vienna quella volta. Ma strane circostanze mi riportarono lì.

E li sono ora. E così cammino attraverso Vienna, con Peter e mentre cammino

mentre attraverso le gallerie attraverso i monasteri e Dehmel: attraverso le

cantine di vino e tra le botti di vino, _io incominciai di nuovo a credere

nell’indistruttibilità dello spirito umano; in certe qualità, in certi

standard che sono stati stabiliti dagli uomini attraverso secoli e saranno

qui quando noi non ci saremo più.

Stemmo

lì quella notte d’agosto a Kremsmunter pochi amici sul tetto di un

monastero vecchio milleduecento anni e mentre la notte stava arrivando il

sole spariva; una luce blu cadeva sopra il terreno. Era tutto pieno di pace.

I nostri cuori e le nostre menti erano inebriate.

Sulla nostra strada di ritorno a Vienna da lontano vedemmo un fuoco. Vienna stava bruciando. Il mercato della frutta stava bruciando Peter disse che era un peccato. Egli disse che era il più bel mercato di Vienna. Disse che la città gli aveva dato fuoco deliberatamente per ricavarci qualcosa. Essi volevano in mercato più moderno.”

[17] Sitney, P.A., The Avant-Garde Film op. cit., pag. 196.

Traduzione: “Decisi più tardi dopo aver girato che tipo di sonoro usare. Avevo collezionato sonori in tutti i posti. Normalmente finisco con certe immagini e certi suoni riprendono la stessa situazione. Li guardo alle mie riprese come memorie, come note e nello stesso modo guardo al sonoro collezionato in quel periodo. Nel caso poi della musica per la parte lituana di Reminiscences è solo una coincidenza che ricevetti una cassetta che ammiravo molto. Essa contiene musica scritta intorno al 1910 da un giovane compositore-pittore lituano di nome Ciurlionis che morì giovane in manicomio. Registrai certi passaggi ripetutamente di questo. Ci devono essere influenze di Scriabin in esso (questo è quello che dicono alcuni) ma essenzialmente essa è musica lituana. Ci sono alcune note in esso che mi parlavano e li ascoltavo spesso fino a quando il disco mi fu rubato assieme alle fotografie circa dieci anni fa. Così è per questo che questa musica significa qualcosa per me, mi è molto vicina, ed è per questo che la usai. La usai come un cappio per un certo verso. Pensavo mi avrebbe aiutato ad unire tutti i pezzi insieme per via di questo suono . Usai Bruckner per la sequenza con Kubelka a Vienna perché egli era uno dei suoi compositori preferiti. I madrigali usati nella biblioteca Kremsmuenster sono tra i preferiti di Kubelka. Così è tutto molto personale.”

[18] Ibidem, pp. 193-194.

Traduzione: “Nel caso di Reminiscences il montaggio fu molto veloce. H. Brecht della televisione tedesca mi aiutò a pagare per la pellicola e la cinepresa in cambio del fatto di mostrare le riprese su una televisione tedesca. Ma quando tornai a casa, mi dimenticai completamente di questi. Ed egli si dimenticò di me. Poi a natale egli mi chiamò “E’ pronto il film? Ne ho bisogno per il venti gennaio” “Il venti gennaio? Perché non mi hai avvisato prima?” Mi sedetti al mio tavolo di montaggio ed iniziai il lavoro. Dopo essere tornato a casa avevo iniziato a pensare: “Come lo monterò? Queste riprese mi erano molto care. Non avevo nessuna idea. Ed anche oggi ne ho poche idee. Possedevo circa il doppio dei fotogrammi che si possono vedere nel film. Così ero lì e mi dissi: “Bene molto bene Questa emergenza mi aiuterà a prendere una decisione” Per due o tre giorni non toccai il materiale, pensai soprattutto alla forma, alla struttura da dare al film. POI una volta decisa la struttura gli diedi una forma velocemente in un giorno. Sapevo che questa era l’unica maniera per arrivare ad un risultato: lavorando cioè in modo totalmente meccanico. Un altro modo sarebbe stato lavorarci su a lungo, e creare un film del tutto differente, oppure distruggere tutte le riprese nel processo di costruzione.”

[19] Ibidem, pag. 194.

Traduzione: “Ma in qualche modo quando fui lì non riuscii a lavorare con lo stesso stile di Walden. Più a lungo stavo lì più cambiavo e ciò mi portò ad uno stile diverso. C’erano sentimenti, stati d’animo e facce che non potevo riprendere in modo astratto. Certe realtà possono mostrarsi nel cinema solo attraverso certe durate. Ogni soggetto ogni realtà ogni emozione risente dello stile con cui tu giri. Lo stile che usai in Reminiscences non fu il più perfetto. Esso fu uno stile di compromessi.”

[20] Ibidem.

Traduzione: “In realtà essa era difettosa, non teneva mai la stessa velocità. La preparavo a ventiquattro frame e dopo tre o quattro riprese si spostava a trentadue frame. Bisognava costantemente tenere d’occhio il metro di velocità perché questo cambiava anche la luce e l’esposizione. Quando alla fine mi resi conto che non c’era modo di fissarla decisi di accettarla ed incorporai il difetto come una decisione stilistica e di usare il cambiamento di luce come significati strutturali.”

[21] “Technique Mars Movie” in Daily News, March 4, 1974

Traduzione: “e questo è l’ultimo film pieno di lampi e cattive esposizione con movimento di macchina sconnessi che mi hanno costretto ripetutamente a chiudere gli occhi e mi hanno provocato la nausea. La confusione delle immagini nasconde le emozioni e lascia lo spettatore esausto ed annoiato.”

[22] “Reminiscences Of A Journey To Lithuania”, in Variety, November 10, 1972.

Traduzione: “Gli aspetti tecnici di questa articolata visita cinematica sono talmente brutte, montate instabilmente, girati con sovraesposizioni, con continue ripetizioni, con più il fatto che non succede proprio nulla, risulta essere una fatica inutile che ci porta alla conclusione che la sua selezione al festival è stata fatta senza averlo visto.”

[23] “Home movie of homelessness”, in The Village Voice, November 2, 1972.

Traduzione: “una vittima casuale di convenienti programmazioni e poco ingannevoli marche.

[24] Canby, Vincent, “Film Festival: Saga of Homecoming”, in The New York Time, October 5, 1972.

Traduzione: “Il programma creato per una serata più piena di Mekas di quanto uno avrebbe mai voluto, essa è poi diventata indulgente, bellissima poetica banale ripetitiva e coraggiosa e fortemente personale. Sebbene Reminiscences cosa stare da solo, esso rappresenta una continuazione dei diari nello stile e nei modi. Sebbene abbia detto ciò neppure al fratello fu permesso di vede il film dell’altro prima che fosse completato, il film di Adolfas serve come un omaggio al film di Jonas. Reminiscences è un film molto interessante e ben selezionato, più che una registrazione di una vacanza di Jonas Mekas. Esso è una testimonianza di tutte le persone deportate geograficamente, come lo sono stati i fratelli Mekas e spiritualmente.”

[25] Bannon, Anthony, “Mekas Film Touching, Refreshing”, in Buffalo Evening News, December 12, 1972.

Traduzione: “Reminiscences il nuovo film di J. Mekas è un toccante lavoro di purificazione e nutrimento, il diario filmato di un uomo che torna nella terra natale dopo venticinque anni di assenza forzata presentato con un impulso cinematografico che permette a tutti di vederlo senza l’imbarazzo del sentimentalismo”

[26] Edstrom, Mauritz, “Jonas Mekas fran Litauen berattar om en resa hem” in Dagens Nyheter, 24 / 7, 1972.

Traduzione: “Il film di J. Mekas rappresenta un’investigazione delle scene giovanili di un essere umano, dove tutti gli impulsi principali erano ottenuti. Le memorie che mantengono i sentimenti per un’altra patria accompagnano le immagini attraverso un testo concreto, sensuale ma mai sentimentale. Reminiscences non ha nulla della normale perfezione tipica di molti film. Ma esso ha qualcosa di meglio: un alito di vita. Esso fa parte di quei film che ci fanno venire voglia di andare al cinema.”